tl;dr: YouTube is a strange and collaborative place that enables all kind of different practices on the basis, that every data matters. It is neither your [tube] (we don’t „pwn“ it) nor is it only an imperative to produce and be part of the media economy (you don’t need to tube!). YouTube is a place (in-)between that has to be (level of infrastructure), but can never be (social and ideological level) and thus faces several challenges as a result of its own potential and paradoxes as outlined here.

In the introductory Blogpost we did explore the aims and scope of this blog and the affordances and restrains on my research and its presentation in the classic format of a book publication.

Here, I will discuss YouTube, starting with the promises stemming from its name.

Edit (23.07.2020): This was supposed to be part 1/2 on a YouTube series. Part 2, however, was deemed to be boring and therefore cut out to enable a short discussion on the Shitpostbot 5000.

It’s all about the cat content, isn’t it?

Everybody knows YouTube, or at least „1.5 Billion users are logged in and coming to YouTube every single month“ (YouTube internal Data May 2017 in YouTube Ads). Much is said about „radicalization pathways“ (Ribeiro et al. 2019), the „Making of a YouTube Radical“ (Roose 2019), copyright issues, fair use, transformative content („reaction channels“), abusive/toxic behaviour on the platform etc. Some researches took the cat content to the next level and discussed it, on the basis of the Alchian-Allen Theorem (see Potts 2014).

However, it is not about cats. Or at least only to some degree, since animal videos continue to thrive on YouTube. We are somewhat „content“ with the mapping of society and our world onto this new places (online). Thus establishing connections between them as well as spaces in-between and „new“ cultural practices and places.

Sure, we can make a living on YouTube, run fake news and political campaigns, even by using transformative formats in the language of YouTube and popular culture. Or as a comment says „[a]nother world leader memed into office. God bless the UK“:

YouTube is part of „our world“ and „our world“ is partly represented on YouTube. However, not as „multiple duplications of our world“ (Nassehi 2019; my translation), but as representation of our world in all its diversity and inequality as well as in the creation of new places, forms of representation, practices and agents, yet to be thoroughly explored within the different research disciplines.

But let’s leave all the complexities of our world behind – for now – and focus on the promises within YouTubes name and the things yet to be uncovered: „What is YouTube“ and „Whose tube is it“?

You (are a) tube!

Nearly every article in English about YouTube or generally speaking social platforms starts with the mention of the Time magazine’s „Person of the Year“ from 2006, so here „you“ are too:

„Yes, you. You control the Information Age. welcome to your world.“

I personally feel lauded and important, having featured this prominent position on that magazine, although they did not get my picture right. Almost as with the current situation of the Covid 19 pandemic:

What did we really do to become the „rulers“ of the Information Age? Is it really our world? Or in Beyonce’s words: Who run the world?

This approach entails many essential questions that also need to be represented on the platform accordingly. First comes the critically discussed concept of „person“ and the notion of control and representation of „our“ world in the Information Age.

We could be a „person“, following Esposito’s critique of that term, further modified by Borsò as a „concept of economic order with regards to processes of subjectivation within global capitalism“, so to speak „an subject based on an imaginary empowerment“ (Borsò 2020: 335; my translation).

As with the meme and the cover of Time magazine, there need to be a lot of imagination or narcotic substances involved to imagine oneself as the sole but collective ruler of the Information Age.

In other words, we are nothing but the product of the platform and media economy that needs us as data and content producer, or transformed as meta(data), for their apparatus of consumption. On top of that, we are also required as consumer of our own products, which in itself constitutes nothing but an imaginary empowerment. However true this might sound, it is a pretty grim and possibly unfair outlook in the context of YouTube and its diverse and manifold communities.

Generally speaking, I do however like my fair share of critique of capitalism!

All your data are belong to us!

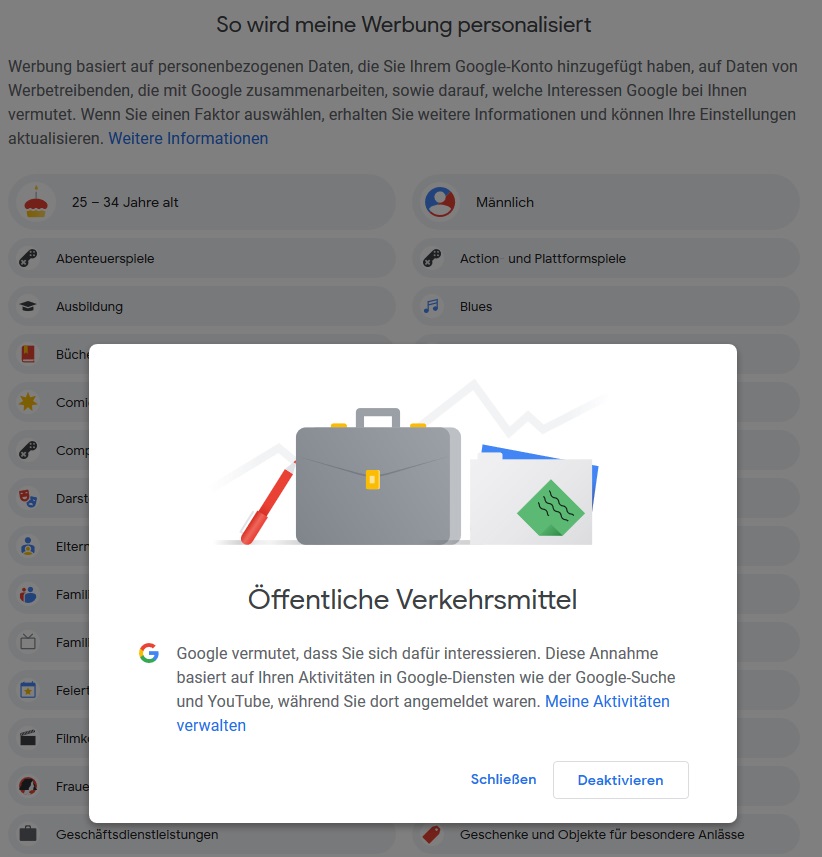

Media and platform economy, as well as consumer content and data, drive the platform and its functions: „You cannot not communicate“ becomes „you cannot not become data“ and thus, you always do „work“ for the platform: steering its recommendation algorithm, modeling (your) user profiles, ultimately feeding back into other Google products and services etc.

This is further highlighted by Bruns (2006) concept of „produsage“ and the categorization of social platforms as „user generated content“ (Van Dijck 2013): We consume and produce not only content but also (meta)data, the fuel of many features on the platform.

On the other hand, our place on this platform does not need to operate as a form of subsistence and dependency: You do not necessesarily need to play the YouTube game, hustling for statistics, growth , audience retention and engagement metrics!

Although expectation of content has been constantly on the rise, leading to more and more requirements on user’s skills in editing and conceptualization of their videos, marketing and SEO strategies, there is lots of room for smaller communities and practices without the biopolitical pressure of trending, growth and economization. This can also be seen by alternative forms of monetization, recurring to an older form in its iteration as a crowd funding practice: The return of the patronage (see Patreon).

Taking all into consideration, the following answer to the question above might not be pertinent but modest:

Yes, we are a tube (as the concept of a YouTube-channel instead of an YouTube-user suggests). But it is not and never was „our“ tube alone. We always had to share this potentially „unlimited“ space and its ressources over which we are made to compete with each other, since they can be monetized (viewers, watch time, subscribers etc.).

However, we do not necessarily need to follow this path, as this place also facilitates many forms of existence, spaces and collaborative practices in paradoxical coexistence with the all-encompasing dispositives of the biopolitical regime.

How many tubes are there? or You(r)Tube is not alone!

Some scholars differentiate this enormous body of spaces (videos) by concepts like the „Two YouTubes“ as grassroot vs. classic media enterprises (see Burgess/Green 2018: 66-72) and cite examples of early TV show on the platform. For example the early inclusion of a Saturday Night Live sketch in December 5th of 2005 (see Burgess/Green 2018: 6).

They argue that the classic „tube“, aka television and media companies, have always been part of YouTube, as well as the big players in the music industry. This can be seen by certain measures, for example the introduction of Content-ID and other policies to protect copyrighted material on the platform (sometimes leading to the dismay of certain Content-Creators and abuse of the system):

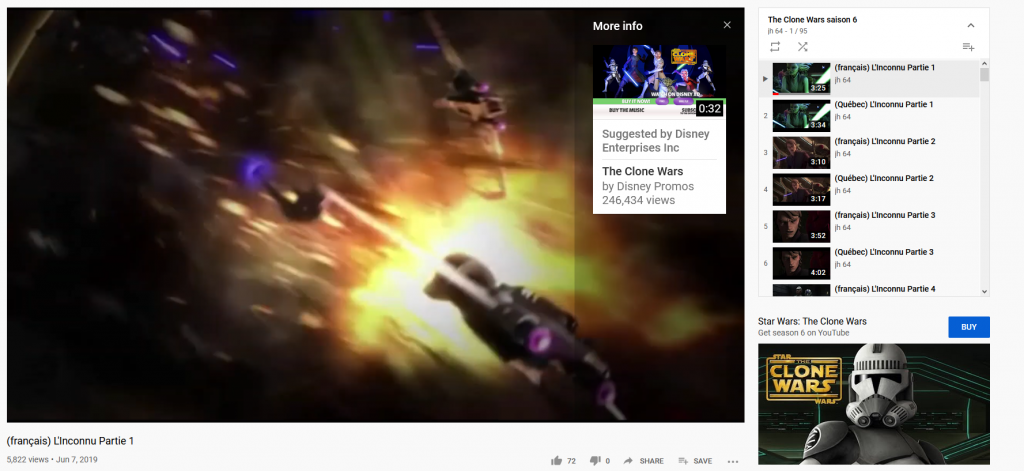

However, systems do not always work as intended and YouTube tends to be far more complex than those exerted dichotomies: old vs. new, online vs. offline, grassroots vs. big media etc. For example, when different monetization strategies meet on the same platform and are activated by transgressive behaviour and user practices: ads vs. renting/buying movies and series vs. pirating/ illegal uploads. Sometimes, YouTube becomes a place to wonder and marvel at the interactions of its systems as well as its user practices:

We can get a glimpse of the proclaimed „convergence culture“ (Jenkins 2006), by the interplay of different systems. This leads – in this case – to a promotional suggestion on a pirated video, that markets itself legally (buy/rent it now on YouTube) on another part of the platform. It is therefore identified by the Content-ID system as property of Disney, that promotes the same content again. A quite peculiar and paradox example, but this is also YouTube as space in-between.

Heal the tube, make it a better place

YouTube is not a bad place by default, since there is enough „tube“ for all of us to carve out and build our own spaces and communities. There is not only clickbait, astroturfing, politics and radicalization to be had, but also creative and passionate people, that open up and share their spaces and knowledge for uninitiated and curious people to behold, also potentially multiplicating this spatial matrix globally (if you dare to do so, I encourage you by watching this Mexican piece of art):

In a way, YouTube is as much „our“ world as is our society or planet: We have to share, to convene, to (dis)agree, to coexist and are ultimately responsible for the sustainability and practices of the places we build for ourselves „online“, as much as we are for our planet, ecosystems and also economies „offline“.

So yes, it is still our tube! But we cannot ultimately tell, how many tubes there are. However, we can observe the processes of negotiating, building and allocating the „ressources“ of this platform by introducing politics, economy and social issues that lead to response and enforcement via the own platform policies (see BBC News 2020). This has been recently brought up again by the discussion about Trumps tweets on Twitters platform (see LegalEagle 2020 below for a legal analysis).

It has not been decided yet, who will ultimately „govern“ this platform or what we actually mean by governing on social platforms, since classic socio-political concepts might not be sufficient or even flawed to adequately describe the dynamics. I personally hope that they will never have to be „governed“. Nevertheless, we can see that there are certain policies introduced that push for the platform to be regulated to a certain degree: misinformation and hate campaigns, piracy and copyright as well as privacy and data protection need to be regulated (see LegalEagle 2020 above). I sincerely hope that this all will still allow for the existence and diversity of „other“ practices and communities on the platform.

Finally, I want to thank you for sticking with me so far and end this post on a positive note with a call to action that features the other side of YouTube as an imperative. Yes it is about us, about you and therefore also our responsibility!

Engage with and build those spaces in a responsible, sustainable and social way:

Sources

BBC News (2020): „Coronavirus: David Icke’s channel deleted by YouTube“. In: BBC News, 2nd of May. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-52517797

Borsò, Vittoria (2020): „Persona oeconomica in der Medienkommunikation: Wider die Anästhetisierung für neue Räume der Medialität“. In: Sieglinde Borvitz (Hg.): Prekäres Leben: Das Politische und die Gemeinschaft in Zeiten der Krise. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Bruns, A. (2006): „Towards produsage: Futures for user-led content production“. In: Proceedings: Cultural attitudes towards communication and technology. Australia: Brisbane, pp. 275-284.

Burgess, Jean / Green, Joshua (2018): YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Cambridge et al.: Polity Press.

Conservatives (2019): „lo fi boriswave beats to relax/get brexit done to“. In: YouTube, 25th of November. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cre0in5n-1E

Jenkins, Henry (2006): Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York / London: New York University Press.

LegalEagle (2020): „Platforms, Publishers, and Presidents ft. HoegLaw (LegalEagle’s Real Law Review)“. In: YouTube, 5th of June. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eUWIi-Ppe5k

Nassehi, Armin (2019): Muster: Theorie der digitalen Gesellschaft. München: C.H. Beck.

Potts, Jason (2014): „The Alchian-Allen Theorem and the Economics of Internet Animals“. In: M/C Journal, 17.2, 1-12.

Ribeiro, Manoel Horta / Raphael Ottoni / Robert West / Vrgílio A. F. Almeida / Wagner Meira Jr. (2019): „Auditing Radicalization Pathways on YouTube“. In arXiv, 4th of December. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1908.08313.pdf

Roose, Kevin (2019): „The Making of a YouTube Radical“. In: New York Times, 8th of June. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/06/08/technology/youtube-radical.html

Saturday Night Live (2013): „Lazy Sunday – SNL Digital Short“. In: YouTube, 17th of August. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sRhTeaa_B98

Van Dijck, José (2013): The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

YouTube Creators (2010): „YouTube Content ID“. In: YouTube, 28th of September. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9g2U12SsRns

Neueste Kommentare